December Issue #2

How worried should you be about disappearing snowpack?

I hope your elf on a shelf survived another week from the family dog, and your Q4 projects are coming to an end. We’ve got a lot to cover, so pour that coffee and keep reading. This week’s deep dive focuses on the impact of low snow years on water storage.

A quick recap of what we learned last week:

Snow Drought is a period of abnormally low snowpack for the time of year in question

The West’s water infrastructure relies heavily on snowpack which typically acts as a natural reservoir

Implications on Summer Water Availability

Snow droughts reduce the amount of available water for spring and summer snowmelt, shifting streamflow timing and reducing soil moisture. For decades, snowpack has served as a vital source of natural water storage. As snowpack declines, we lose that built-in water storage capacity, posing significant challenges for water management, ecological health, and natural hazards including wildfire. Modeled projections indicate large declines in snowpack across the Western US and a shift to more precipitation falling as rain rather than as snow during winter months.

Where does this leave us?

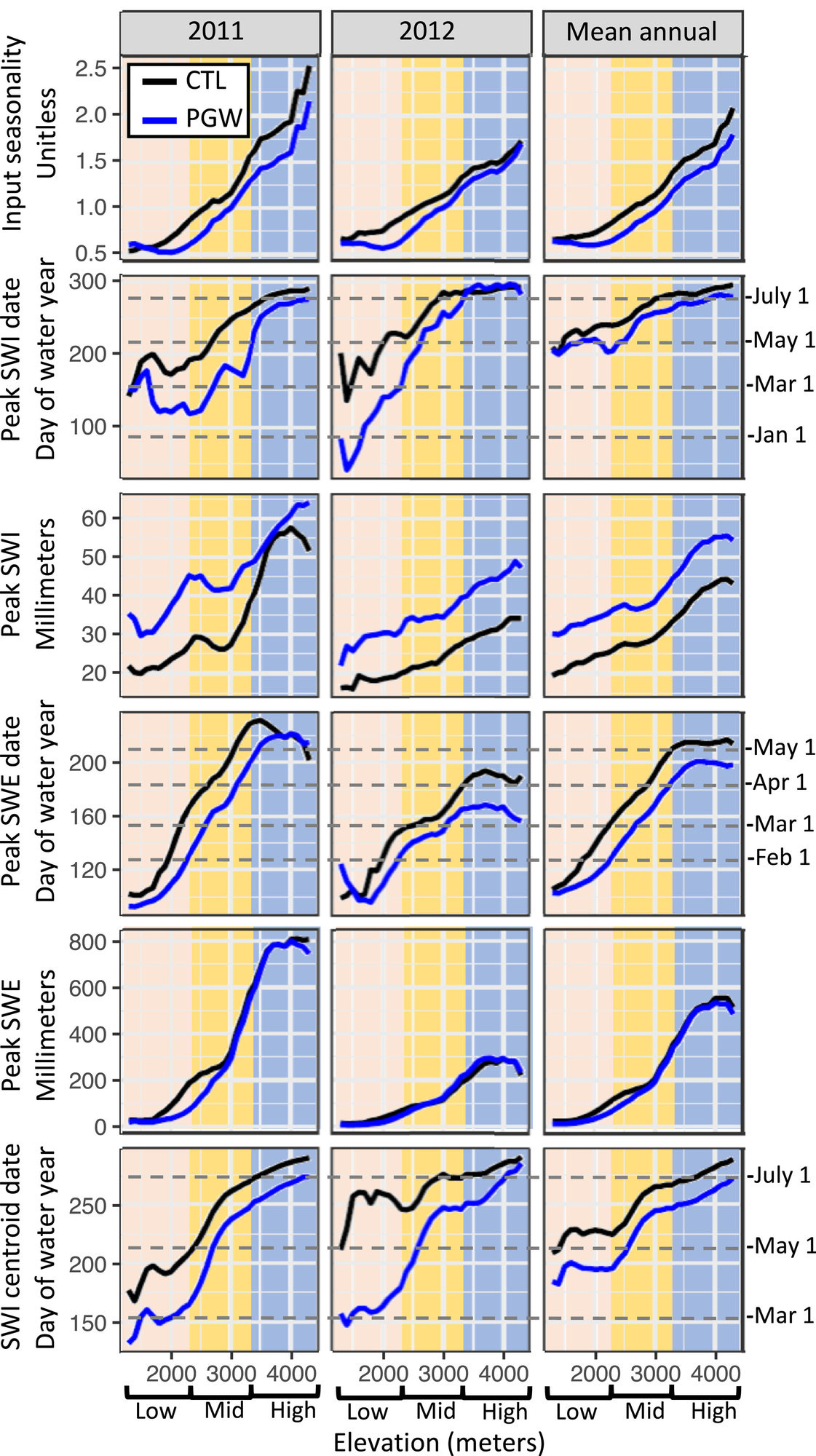

A 2023 study modeling study of the Upper Colorado River Basin found that declining snowpack will shift water availability earlier in the season and concentrate it into a narrower window of time, creating “flashier” surface water input rather than the gradual, extended melt that has historically provided steady summer water supply.* This elevation-dependent snow loss fundamentally changes when water becomes available to downstream users and ecosystems.

However, streamflow responses to snow drought remain uncertain. Reductions in snowpack during snow droughts affect catchment liquid water input (LWI), which shapes seasonal and annual streamflow patterns. Yet studies disagree on how streamflow ultimately responds in winter-affected regions. Many report that lower snow accumulation and diminished melt decrease warm-season streamflow, reducing annual totals when precipitation remains unchanged. Other research suggests that shifts in snow dynamics do not necessarily reallocate water supply from summer to winter, and that annual streamflow may remain relatively stable. These inconsistencies stem partly from differences in how seasonal LWI is controlled across different snow drought types.

A key gap remains: there is limited observational evidence showing how LWI and streamflow respond to different snow drought types, leaving their impacts on seasonal and annual streamflow not well constrained. Better understanding these responses will be critical for water planning in a warming climate.

*Water arrives more quickly and concentrates into a shorter, more intense peak rather than spreading out gradually over time.